Even The Wall Street Journal is in on the artificial…excitement…act. Congress has just a few days to pass a bill before June 5 deadline goes the subheadline.

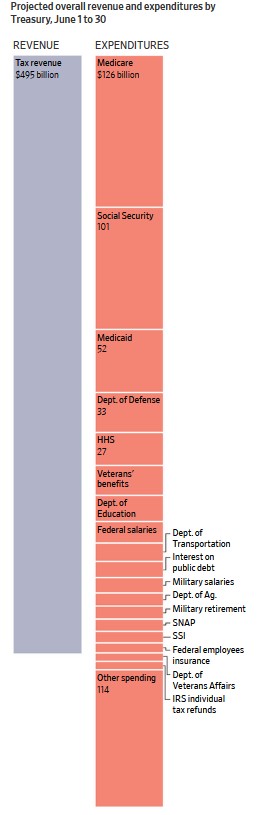

It’s not much of a deadline, with revenue flowing in under existing tax laws that’s more than sufficient to pay as scheduled the principal and interest on our nation’s debt, and then the scheduled payments for our soldiers and veterans, and then the scheduled payments for Social Security and Medicare along with the scheduled transfers to the States for Medicaid, and then the scheduled payments for HHS, then DoT (for good or ill), then DoEd (for good or ill), then….

You get the idea.

There are only a couple of things of note should a debt ceiling deal not be enacted by 5 June (or whatever becomes Yellen’s deadline du jour). One is that much of the Federal government would have to shut down. That amounts to a big so what.

The other is that a number of Federal government contracts with private businesses would have their payments HIAed, to the detriment of those businesses. The failure to pay on time also would strongly negatively affect our economy and to a large extent our reputation around the world.

That last is a consideration worth taking very seriously, but not at the expense of enacting a debt ceiling deal, any deal. Republicans and Conservatives in the House need to stand firm. The present deal isn’t all that, but, to coin a phrase, think of the (Progressive-Democratic Party’s) alternative.

The deal also shouldn’t be stand-alone.

Some conservatives in the House and Senate have said they would oppose the deal because it doesn’t go far enough to limit federal spending….

One way to show they’re serious about that is via the as yet undeveloped Federal budget for the next fiscal year. Beginning Thursday (assuming today’s vote is up rather than down), the House—which is to say, the Republican caucus, since they’ll get no cooperation from the Never-and-Nothing-Republican Progressive-Democratic Party caucus—needs to begin work on that next Federal budget, a budget that codifies reduced Federal spending, reduced Federal tax rates, and reformed Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid transfer payments, and have that budget passed and ready to send to the Senate the day after that body votes on the debt ceiling bill.

And then the House—the Republican caucus—needs to get to work on the dozen separate appropriations bills that are due by this fall.

There’s no need to wait on a President’s budget proposal (what President Joe Biden (D) tossed over the House’s transom this winter is not one that can be taken seriously) or to put up with Progressive-Democrat obstructionism and knee-jerk “No.”

Press ahead.