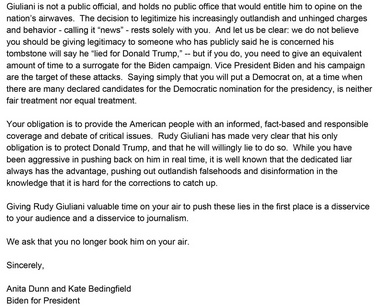

We’re beginning to see more of the value system that the most progressive candidate of them all, Progressive-Democratic Party Presidential candidate and ex-Vice President Joe Biden, wants to impose on all of us. His campaign team, led by Anita Dunn (one of ex-President Barack Obama’s early White House Communications Directors) and Kate Bedingfield (Biden’s 2015 Communications Director) of Biden for President, have written to

executives and top political anchors at ABC, CBS, CNN, Fox News, and NBC, including star interviewers like Jake Tapper, Chuck Todd, and Chris Wallace

to demand all of them cut Rudy Giuliani out of his ability to speak to us ordinary Americans via those widely disseminated and watched programs.

We are writing today with grave concern that you continue to book Rudy Giuliani on your air to spread false, debunked conspiracy theories on behalf of Donald Trump.

Giving Rudy Giuliani valuable time on your air to push these lies in the first place is a disservice to your audience and a disservice to journalism

This is as clear an expression of the contempt in which members of the Progressive-Democratic Party hold us ordinary Americans. Plainly, they think us just too grindingly stupid to decide for ourselves what we’ll listen to or how to think about what we hear, including whether Giuliani’s comments really are false, debunked conspiracy theories. Or whether it might be Biden, et al., who are distorting the facts. Biden, with this letter that The New York Times go hold of, has made that contempt explicit. Again.

Much worse, though, is that this is a demonstration of the overall nature of free speech that the Biden the Presidential candidate is pushing. Think about the breadth and depth of his assault on our freedom of speech that a Biden administration would inflict on our nation.