Spiegel Online International carried an interesting article the other day. They cited the Institute for New Economic Thinking as saying

We believe that as of July 2012, Europe is sleepwalking toward a disaster of incalculable proportions….

Paraphrasing them, SOI went on to say that the European leadership must move faster and more decisively, else the euro could simply disintegrate. The INET report can be read here.

SOI went on, noting that

The experts wrote that the crisis is the result of flawed design, construction and implementation of the finance and currency system. In order to rescue it, the economists are calling for a radical restructuring.

And here are the changes these experts want:

- tighter integration of the financial system with a strong institution at the European Union or euro-zone level that would make stabilizing the banks a matter for all of Europe;

- the permanent euro rescue fund, the European Stability Mechanism, to be provided with a banking license as a lender in order to give it the “firepower” that it needs;

- the European Central Bank to better use all the tools at its disposal (both conventional and unconventional) in order to bolster the currency union.

Then these experts claim, contradictorily, that none of this

mean[s] that the costs of the crisis should be socialized across euro-zone citizens: systemic failure does not absolve from responsibility individuals, banks and supervisors who took or oversaw imprudent lending and borrowing decisions.

This much is correct, but each of those three steps specifically socialize the costs of the present crisis across “euro-zone citizens.”

Even the illustrious Secretary General of the OECD, Angel Gurria, thinks much of this is a good idea, insisting that the ECB should get back into the business of buying bankrupt countries’ junk bonds

more decisively and with bigger numbers…you have to stabilize the yields.

Gurria added that he saw no reason why Italy and Spain should be paying yields of 7.5%. Here he shows the typical mindset of a European government man: the market has said these bonds have value only at those yields. Why should individual taxpayers be forced to indemnify them at a lower yield? Because a Government Man Knows Better.

None of these measures can succeed, though, since they proceed from a wholesale misunderstanding of what is necessary for effective integration of polities: comity of social purpose, common understanding of the role of government in the lives and economies of free men, common understanding of the purpose of money. These do not obtain in the EU as a whole, nor in that subset that is the eurozone. The whole of southern Europe has an entirely different view of the role of government and of money, wholly differing social imperatives than those of northern Europe. And these nations radically differ in their views from the concepts extant in eastern Europe. And France and Great Britain differ—in their unique ways—from all of these. Absent greater political and social moral imperative agreement, there can be no successful “eurozone.”

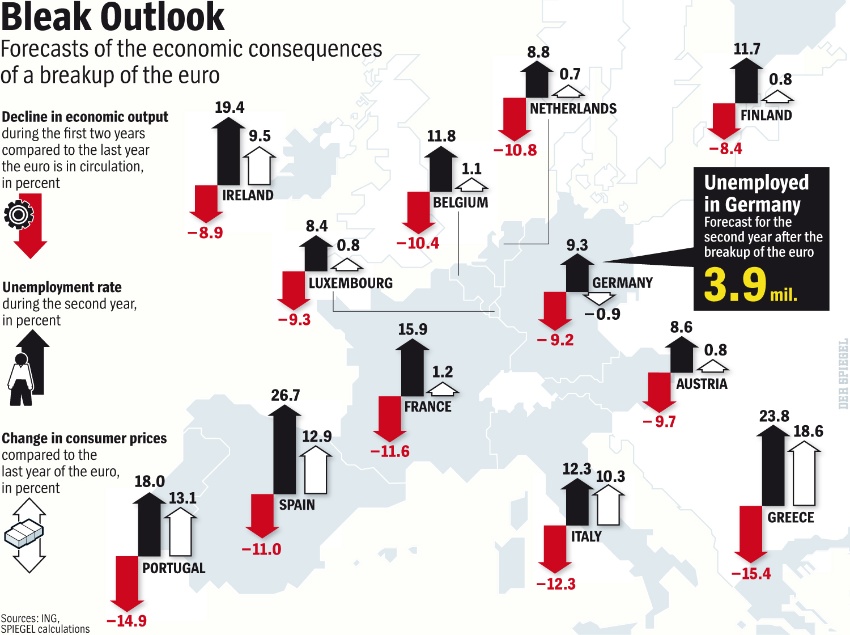

There is a lesser false premise from which INET (and the others) proceed: that the breakup of the Eurozone would be a “disaster of incalculable proportions.” The only disaster here would be to the various subsets of Europe forcibly carved up and jammed into the eurozone’s Procrustean Bed, and to the egos of those married to the Eurozone as it is constructed.