House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan’s “Expanding Opportunity in America” proposal can be seen in full here. I’ll only comment on parts of it in this post.

On the 50th anniversary of the War on Poverty, then, we should reexamine the federal government’s role. For too long, the federal government has tried to supplant, and not to support, the people fighting poverty on the front lines—families, neighborhoods, community groups. In the fight against poverty, the people ultimately are the vanguard, and government is the rearguard. Government protects the supply lines. But it is the people themselves who take to the front lines.

A major part of his proposal is his Opportunity Grant Pilot-Project

[T]his proposal [The Opportunity Grant Pilot-Project] would create a new pilot project in a select number of states. In participating states, the federal government would consolidate a number of means-tested programs into a new Opportunity Grant (OG) program. The largest contributions would come from SNAP, TANF, child-care, and housing-assistance programs, and the funding would be deficit-neutral relative to current law.

It is important to note that this is not a budget-cutting exercise—this is a reform proposal. This consolidation does not make judgments about an optimal level of spending. Instead, this proposal is concerned with our ability to use resources effectively and to find out what works. It allows the federal government to leverage its strengths—vast resources—while also allowing states, localities, and communities to leverage theirs—deep knowledge of their population and the unique challenges they face. Therefore, this proposal seeks to create the space and flexibility necessary for local, state, and federal government to add value without making judgments about the right level of spending.

OG Funding Stream

Consolidates several means-tested programs into a new Opportunity Grant program.

Each participating state gets the same amount of funding they receive from the programs listed in Appendix I.

The proposal is deficit-neutral relative to current law.

Within the Opportunity Grant, states would have flexibility in accommodating housing-aid recipients, the elderly, and the disabled—either by maintaining the current programs or dedicating the same amount of resources to them in the new program.

He offers, though, few ideas on how this program would eliminate the welfare tax cliff he mentions and that’s also described here. “Sign a contract:”

Providers must be held accountable, and so should recipients. Each beneficiary will sign a contract with consequences for failing to meet the agreed-upon benchmarks. At the same time, there should also be incentives for people to go to work. Under each life plan, if the individual meets the benchmarks ahead of schedule, then he or she could be rewarded. For example, if the goal of an individual’s plan is to find a job within six months, and he or she starts working within three months, he or she could receive a bonus. Bonuses could take a number of creative forms, such as a savings bond.

He offers no examples of how this might work; he relies solely on the hope that State experimentation will suffice. This isn’t all bad, if only for the admission that the Federal government has no solutions—and that’s the point of his entire proposal. It’s also not a forlorn hope: State experimentation is necessary; it’s there that the answers will be developed.

Of course the Progressives in government will not like this plan: it encourages people to see to their own ends, it enables them to become responsible, independent, contributing citizens, and it will end their dependency on the welfare handouts of Progressives—it will reduce the need for those whose jobs, political or bureaucratic, depend on being able to provide welfare handouts.

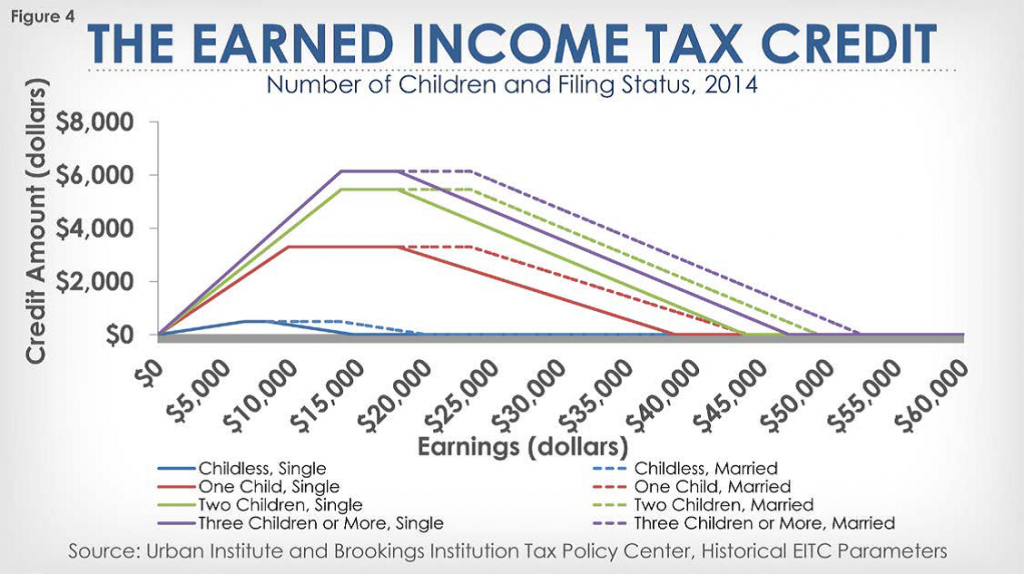

Regarding Ryan’s Earned Income Tax Credit expansion, I confess to misgivings here, too, although Ryan’s proposal makes sense as a first cut. I’ve never been enamored of this; it’s hard to see how the welfare cliff from losing the credit in return for advancing in work isn’t a discouragement from finding advancement in work. However,

The consensus among independent economists is that in most cases the EITC makes low-income families more likely to work by increasing work’s rewards. CBO also finds that it encourages households to enter the labor force.

Ryan’s proposal is simply to expand EITC eligibility to younger workers and to childless single and married parents (not to raise the upper income bound for eligibility), and to pay for that expansion with spending cuts—real cuts—elsewhere in the budget.

Ryan’s proposal is simply to expand EITC eligibility to younger workers and to childless single and married parents (not to raise the upper income bound for eligibility), and to pay for that expansion with spending cuts—real cuts—elsewhere in the budget.

Running the numbers seems to mitigate the other part of this: that discouragement from advancement through the reduction in EITC subsidy that results. A married couple, one child family, for instance, making $25,000/yr gets roughly $3,500 in EITC for total income of $28,500. Were that family gets a wage increase to $30k, EITC falls to a rough $3k for total income of $33k. Thus, the family would keep $4.5k of that total income increase; the drop in EITC would constitute only a 10% “tax” on that raise.

Federal criminal justice system

Ryan’s proposal here centers on sentencing and prison reform, and this is good. A couple things are lacking, though, regarding sentencing. One specific sentencing reform that would be valuable—and that would dovetail nicely with his jobs training proposal—regards nonviolent criminal sentencing. This should center on community service, but not just any service: the criminal’s time here should be in a service that also teaches the man a marketable skill, so that when he’s finished paying his debt for his crime, he’s not only a free man again, he has the means with which to earn his way through life, rather than (be forced to) resume stealing it.

The other reform here will be much harder to achieve, and in truth it’s outside the scope of a budget proposal. We have too many Federal laws on the books, and in particular, we have too many Federal criminal laws. These need to be culled.

In the end, there’s much not to like in Ryan’s proposal—it’s deficit neutral, for instance; it by design leaves spending and taxing alone—but there’s also much to like. Progressives in government won’t like it, either. It reduces the Federal government’s role in our economy and in our individual lives, and from that it reduces those Progressives’ raison d’être.

The largest likability, and this alone is a deal maker, is that it’s a net improvement over the existing welfare régime: it takes control over welfare away from the Federal government, which for all its good intentions is too remote and too slow to respond to changing conditions, and puts welfare in the hands of those closest to the particular welfare needs: the State governments and local agencies.

Ryan’s proposal does this—another strong likability—by reallocating existing spending into consolidated block grants and shipping those to the States. The strings attached to these grants—and I’m of mixed minds regarding any Federal stringing—are minimal and centered on satisfying a Federal agency (primarily HHS and Education) that a State’s plans for the grants are suitable to the task.

****

Finally, we also must be mindful of two things: the first is that better is the enemy of good enough. This plan is good enough, for today. This plan is good enough as a first step.

The other thing is a direct follow-on to the first: welfare reform—nothing in politics—is a once and done affair. Most discussions of welfare reform, tax reform, spending reform, what-have-you reform only look at a specific proposal as though it’s entire in itself and nothing more need be done, or rejected. It’s not good enough now, so toss it and start over.

This plan is not fully grown or perfect, either. But it’s good enough for now. It’s good enough (since passage in 2014 is unlikely) for next year, and that year’s status as the first year of the 114th Congress. Pass it, knowing that the work isn’t done and knowing that the work can be improved. Then come back the following year, the second year of that Congress and correct the defects that will have become apparent by then, and add to the plan additional, de novo, changes as the experimental results come in, as experience suggests new ideas. Then in each of the sessions of the 115th Congress, do it again. And again in the 116th. And so on.