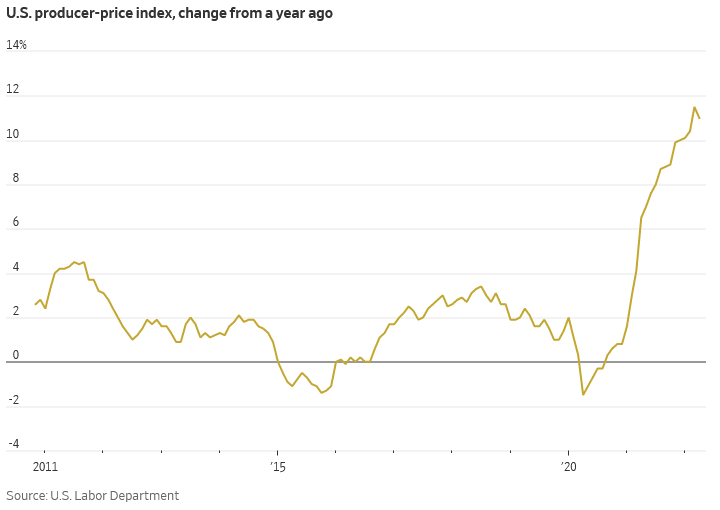

Illustrated in two graphs. The first is the overall Producer-Price Index performance over the last 11 years.

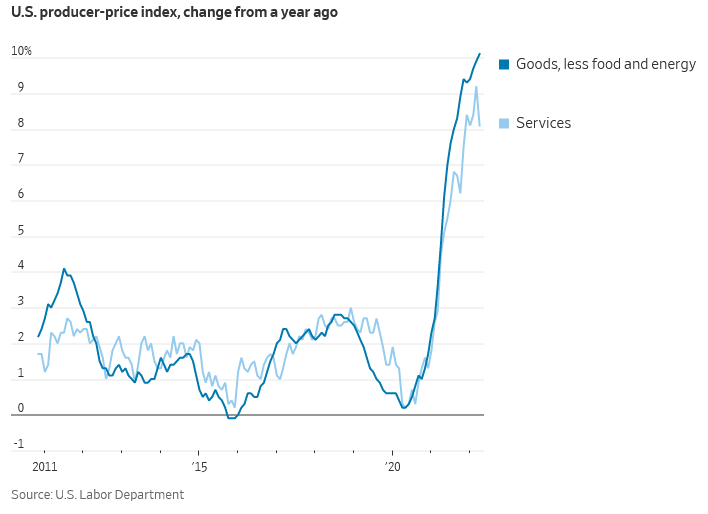

The second breaks out services from goods, the latter absent food and energy.

Now certainly, in addition to the immediacy of expectations, there are lags of some weeks to months in our economy, and it can take time for policies to have impact.

Oh, wait—notice those periods before the current inflation began spiking: the PPI was declining through the year-and-a-half before President Joe Biden (D) won the election. The PPI began its sharp rise right after that on expectations of Biden’s policy implementations, and it continued unabated as those expectations were realized and began their material impact on our economy.

Look, too, at the steadiness of the PPI rise. Neither supply chain disruptions nor Putin’s war have had any impact on the inflation rise. Look again at the 18 moths preceding Biden’s election. The pandemic, too, is wholly irrelevant to this hard rise.

This round of inflation really is Joe Biden’s fault, no matter how deeply he ducks under his desk, or how many times he scurries off to Delaware to avoid facing us average Americans.