The Congressional Budget Office pipes up. Here’re some highlights from its January 31 annual Budget and Economic Outlook.

The current-law baseline which the CBO uses is a set of budget projections based on existing law as enacted, including sunsets and expirations. These assumptions thus accept, for instance, that all temporary tax provisions, including those originally enacted as part of the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 and the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003—the Bush tax cuts—will expire as scheduled and that the alternative minimum tax (AMT) will not be indexed for inflation past 2011. Further, under these baseline assumptions, about $1 trillion of spending cuts that mandated under the Budget Control Act of 2011 following the failure of Congress’ supercommittee will begin as scheduled in January 2013.

What flows from this baseline? The budget deficit falls from the current year’s nearly $1.1 trillion, or 7.0 percent of GDP, to 1.5 percent of GDP in fiscal 2015—primarily due to an optimistic 25 percent increase in total federal revenues during that period. The CBO cautions, though, that the deficit will resume its expansion post-2015 due to mandatory spending on programs such as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid and increasing interest payments on the still expanding federal debt.

The CBO also offered estimates based on an alternate scenario and its assumptions. In its “alternative fiscal scenario,” the CBO assumes that the expiring Bush tax cuts are extended (excluding the current 2% payroll tax holiday); the AMT is indexed for inflation post-2011; Medicare physician payments are held constant at current levels (rather than falling nearly 30 percent in March 2012); and the spending cuts required under the Budget Control Act do occur.

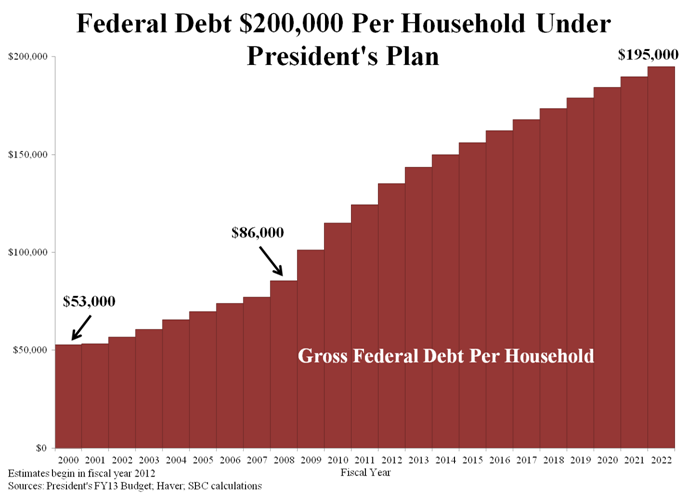

Using these assumptions, the CBO concludes that annual budget deficits will remain elevated at about 5.4% of GDP over the next 10 years, and the ratio of publicly held debt to GDP will rise from its current elevated level of nearly 72% in fiscal 2012 to over 94% in fiscal 2022.

There are other aspects to this. The CBO estimates that with the Bush tax cut expiry, economic growth—GDP growth—will be a meager 1.1% until recovery can begin in the out-years. On the other hand, were these alternate assumptions enacted, GDP growth would be 0.3 to 2.9 per centage points greater than under current law. Later in the decade, though, higher levels of government borrowing would crowd out private investment, drive up interest rates, and hold back economic growth.

Notice what’s not being assumed in the alternative scenario: real cuts in spending. The assumptions don’t even include the effects of the fictional cuts of “reduced increases” in future spending. What is it that drives that “higher level of government borrowing?” It’s not not enough revenue for the government. It’s too much spending by the government.

When, and only when, government spending is reduced to sane levels can we begin to pay down our burgeoning national debt. Only by leaving our money in our hands and not having it taken away from us by ever-increasing taxes and by ever-increasing debt payments can our private investments increase, our job creation increase, our prosperity begin to recover.

h/t: Deloitte