I wrote last fall on this subject. Even though a new round of bailout funding is being discussed, my argument hasn’t changed. Now, though, Spiegel Online International reports that it appears that European leaders are beginning to recognize the folly, as well: it’s best to cut the Greeks loose to find their own way, and to find their freedom from the fiscal bondage that ever-increasing debt and continued Greek resistance to making serious spending cuts are creating. Yet the majority continue to cling to their asserted need for bailouts.

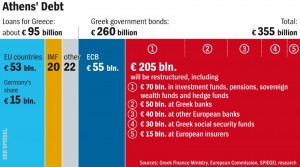

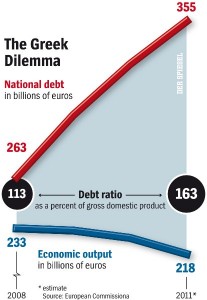

Everyone knows that Greece cannot repay its massive pile of debts, now at more than €350 billion ($459 billion). But instead of effectively reducing the financial burden, European politicians intend to approve new loans for the government in Athens and go on fighting debt with new debt. “If the country wants to remain in the euro zone, we should support it,” says Austrian Chancellor Werner Faymann.

And

If there are no other options, says Luxembourg Finance Minister Luc Frieden, “the public sector may have to provide more money.”

And

The representatives of the so-called troika, consisting of the European Commission, the European Central Bank (ECB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), estimate the shortfall [for the second round of bailout payouts] to be about €15 billion, meaning that Greece needs €145 billion instead of €130 billion.

The only other option is to redistribute the burden. Under the current program, the IMF is responsible for about one-third, and the Europeans for two-thirds of the costs.

But these illustrate the depth of the Greek problem, and the inability of additional borrowing, of additional bailouts to solve the problem.

With the Greek debt exploding and its economic output shrinking, if not actually collapsing, there is no hope of repayment—or of growth at all. Furthermore, this leadership school assumes, erroneously, that the “burden” should exist in the first place. And it demonstrates their confusion of who it is that bears this burden. It’s not the EU piggy bank owners from whom the bailout funds are intended to be collected. It’s the Greeks, who are being burdened with even greater debt that they cannot repay, and so with even greater servitude, onto whom this burden is being loaded. It has even been proposed that an external “budget commissioner,” with authority to veto Greek tax and spending decisions, be imposed on Athens.

But others of the political class are beginning to object to continuing the bailout.

[I]n Germany, the main donor country, leading politicians within the two coalition parties, the CDU and the business-friendly Free Democratic Party (FDP), do not believe that a majority of parliamentarians will vote for additional aid to Greece.

More generally,

The German government feels that the financial sector should bear much of the additional burden. If additional funds were needed, the banks would simply have to contribute more, the Germans argue.

This attitude is spreading beyond Germany, too; although without the economic powerhouse of Europe, the future of any more bailing out is highly questionable.

Moreover, the reasons for the growing reluctance, beyond a growing understanding of the folly of bailing out a debt crisis by increasing debt, are becoming more apparent.

The Greek economy is not productive enough to generate growth. Aside from olive oil, textiles and a few chemicals, there are hardly any Greek products suitable for export. On the contrary, Greece is dependent on food imports to feed its population.

“Greece has been living beyond its means for years,” an unpublished study by the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) concludes. “The consumption of goods has exceeded economic output by far.”

And this [emphasis added]:

…lack of progress on austerity measures long-since passed. Attempts to privatize state-owned enterprises, for example, have met with limited success at best. The Greek government initially announced it intended to raise €50 billion in four years by selling state-owned companies and property—a sum that was calculated into the country’s financing needs.

But lack of interest has crippled the program. In 2011, the government’s privatization program brought in just €1.7 billion instead of the €5 billion planned. In 2012, expectations have been reduced from €11 billion to just €4.7 billion. Government-owned enterprises in Greece are simply not competitive enough to attract investors.

A solution is being offered.

Instead, economists recommend finally doing what is already unavoidable: sending the country into an orderly insolvency. Greece’s government creditors, which include the ECB and, most of all, the partner countries that have lent the country money until now, would have to abandon about half of their claims so that the country’s mountain of debt could be reduced to a tolerable level. Then the measures that can return the Greek economy to growth on its own can become more effective: reforms in the labor market, more competition in the service industries and foreign investment.

I’ve insisted all along that Greek bankruptcy is necessary to free the Greeks and give them a new start. If the Europeans think an “orderly bankruptcy” can be arranged, more power to them. However, the success of this, with its continued Greek membership of Greece in the EU and in the euro zone, depends on those follow-on reforms actually be implemented—particularly labor reforms, and one not mentioned: getting all Greeks to pay all of their taxes. I’m not sanguine about either, but especially about the reforms. Nevertheless, bankruptcy is the only way out for Greece, the only way back to freedom and solvency.